Paul Stolper is pleased to announce an exhibition of new monoprints on canvas by Norwegian artist Magne Furuholmen. Entitled Monologues and consisting of 40 paintings Magne experiments with letters, text and written imagery. His artwork is a constant game with the structures of language - a game in which the visual qualities of words are just as important as the semantic meaning of the words themselves.

Furuholmen’s signature is to be found across a wide range of media. As a visual artist however, he is particularly interested in working with various printmaking processes. He enjoys the commitment inherent in the decision-making that occurs in the printing process: “Whatever is sent through the printing-press is irreversible. After the artist has made the decision to print, there is no possible retreat.” Nevertheless, it would be wrong to consider him a printmaker in the traditional sense. A closer look at Furuholmen’s production leaves the viewer in no doubt of the systematic way in which he explores a wide variety of printing methods, often pushing boundaries and making use of the untried potential of a chosen technique, be it etching, monotypes or woodcuts. He often chooses unexpected strategies in order to achieve a particular result, best suited to the artistic concept he is working with.

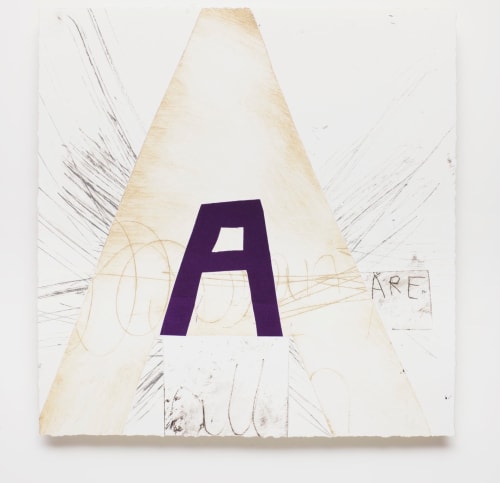

In his new series of images entitled Monologues, Furuholmen has chosen a form of expression more closely connected with painting, although he still employs the printmaking process and technique. The image is painted directly onto a metal sheet, which is then sent through the printing press, where it is transferred onto canvas. In contrast to previous projects, this work has a more painterly aspect to it, but it also represents the continuation of an artistic concept, as the written word is still central to the work.

The canvases are split up into clear, more or less transparent areas of colour. The monochrome letters arrest the gaze, focusing the viewer’s attention on the pictorial surface, stopping any illusion of three-dimensional space. The paintings have a collage-like appearance – they seem to be constructed layer by layer from white, black and brown tones. In some areas however, the artist has chosen to reverse the process; words and sentences have been scraped into the wet paint with the tip of a paintbrush.

Monologues follow a long tradition of using text or letters in painting and printmaking. Around 1911, Georges Braque began experimenting with stencilled letters and numbers on his canvases with a view to drawing attention to the surface of the painting. Ten years later the DADA artists, such as Kurt Schwitters and Hanna Höch extended and developed the art of collage using the technique of montage, combining photographs and other visual imagery with words and quotations from the written media. The Lettrists of the 1950s, in particular Isodore Isou and Guy Debord, used words, letters and signs to achieve visual effects. The idea behind this was to break down the boundaries between the various art forms – especially between painting and poetry – using the alphabet as a starting point.

The double role that letters play – as purely visual objects and as components of words with specific, semantic meanings, seems particularly important in Monologues. The letters hint at words, and where the words are recognisable, they in turn hint at whole sentences, without disclosing the complete meaning. Simultaneously – and without losing sight of the literary meaning of the word itself – the shape of each letter creates and recalls other images and feelings. The fact that Furuholmen is also a musician leads us to yet another reading of the work – the onomatopoetic perspective; signs that imitate a particular sound or audio-image.

Just as the Lettrists combined painting and poetry, so Magne Furuholmen – visual artist and musician – examines the ways in which he can create a resonance between the media:

“Previously I have focused most on sound and visualisation, but more recently it has become important for me to work with words, the meaning of words, and formulation (…) to work in several different media simultaneously gives me the possibility of studying, and to a certain extent of “opening” the work, by exposing it to different kinds of treatment – and perhaps learn more about it.”