Fiona Banner

Don’t Look Back, 1999

Stamped FB lower right on one print

3 silkscreen prints on paper

Unique

Unique

Sheet size: 100 x 70 cm

Frame size: 105 x 75 cm

Frame size: 105 x 75 cm

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

Comments: One of three sheets stamped FB

Comments: One of three sheets stamped FB

Provenance

Swop

Literature

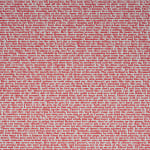

The Guardian - Precious memories | Saturday December 4, 1999Fiona Banner, an artist born in Merseyside in 1966, has made a variety of works that explore the relationship between images, particularly filmic images, and words. For her 1997 work The Nam, for instance, she wrote detailed, unedited, blow-by-blow descriptions of six Vietnam movies and combined them into one 1,000-page volume. Her latest piece consists of three large panels on which are printed three memorised versions of of the documentary about Bob Dylan, Don't Look Back. Here, she describes how she came to create it:

'Several years ago I had to write a review of a Bob Dylan concert, but couldn't remember anything about the gig at all. Dylan was a phenomenal let down, but it made me realise there's something in disappointment. It's not as bad as we're all led to believe. The headline for the final review was, "You've gotta take the rough with the rough". I still always go to see Dylan if I can. I realise I should have taken notes at the concert, but that would have contradicted the moment.

I have been chasing Dylan for a long time. Dylan was at my sister's bar, but had left in a huff by the time I arrived. He was sound- testing in a pitch-black Hyde Park the night I cycled through after a Serpentine Gallery opening. Security told me to move on. They were testing the lights, and the ground lit up green like seaweed. He was at the Guggenheim in New York City for the launch of a book of his lyrics. I rushed in as the camera flashes went berserk, and I realised he was leaving.

I was desperate one day to watch Don't Look Back, DA Pennebaker's legendary documentary of Dylan's brilliant 1965 tour of the UK. I had just got back from America where I had done a reading from The Nam, and recalled that the film had something to do with the relationship between the American and English languages. I was astounded to find Don't Look Back was now unavailable. It is the first rockumentary, and among the earliest fly-on-the wall documentaries. The film was made in '66, the year I was born. To me it is more like a film without a script than a documentary, and the only film I have seen in which the characters play themselves. Dylan teetering on the edge of mega-stardom, on the brink of inventing rock. Dylan before the media, practising his part in front of the camera.

The film opens with a scene familiar to people who haven't even seen it. It has been mimicked in art, rock video and advertising. It is a meteoric moment in the history of words and pictures, words as pictures. This is the only scene actually in New York; the rest is shot in England. The song is Subterranean Homesick Blues. Did he miss England. Did he miss America? I couldn't write an account of the film, as I had done in earlier works such as Nam. So I tried to describe the film from memory. Here's part of what I recalled:

"He's there in front of the road, and the bearded Ginsberg's at the side, he's holding the cards and his skinny legs taper down to his feet. His hair is like no other. He's wearing a waistcoat. The street is under construction, or perhaps falling apart. He looks out through the front not blinking or caring as he lets the cards fall from his hands, one by one, occasionally looking down to see if the writing on the card, 'government', 'parking meters', 'inkwell', written there in big stoned writing. Words clash with the words he's not singing but are coming out over everything in his voice, like a constant announcement. ‘Medicine', he blinks. One by one the cards slip out of scheme with the words, not that he cares, until he gets to the end, uselessly holding 'that's all', dropping it like throw away and walking off, to leave the bearded one, the rubble and the street."

I always remember in pictures, pictures without edges or particular sequence. I set about remembering the whole of the film, and turned it into words. I have previously described films as total, "completely unedited" accounts. Sometimes these have not only been translations from pictures into words, but, as with The Nam, from American into English.

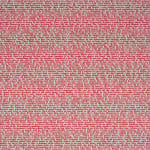

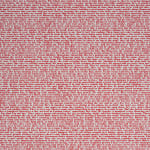

English and American have never seemed so far apart as in this film. Dylan runs rings round the stiff-lipped guys from the Beeb, the uptight manager of a Manchester hotel, the pompous science student who Dylan cajoles with, "You've got a lot of nerve to ask me that_" The rhythm of the American voices renders the starched, self-conscious English laughably absurd. He sings about a wide, open landscape with hobos, but it is always England. He sings about the big sun but it is always night.

I wrote the film out again to see if I could remember any more. It was different but the same. I wrote it again. In the end I had three slightly different versions of the film, all written in the present tense. Paradoxically, memories always come in the present tense - it's the only way you can access them. You never know what you forget, only what you remember. Gradually each attempt to recall the film became a memory, like it was written by someone who was there at those gigs.

I made three versions, which are like something live, as they are recollections, which somewhat contradicts the sentiment of the title! They are reminiscent of something current, live - something always in the present tense, happening all around you. They are like three stages, or performances. Or they are like three audiences looking back at you. Each memory claims to be total, but is contradicted by the next. There is no definitive memory, no definitive description. No two performances are the same. It could go on for ever. But the present sure is tense.'

FB 1999

Don't Look Back., 1999

screen print on paper

Printed by FB at London Print co-op 1999